Join our

next Webinar.

ID fraud has evolved dramatically in 2025. Stolen IDs and genAI fakes are nothing new; fraudsters have found ways to steal real faces, giving them a higher chance of passing high-assurance checks.

This webinar will cover how businesses can use a more strategic approach to signals.

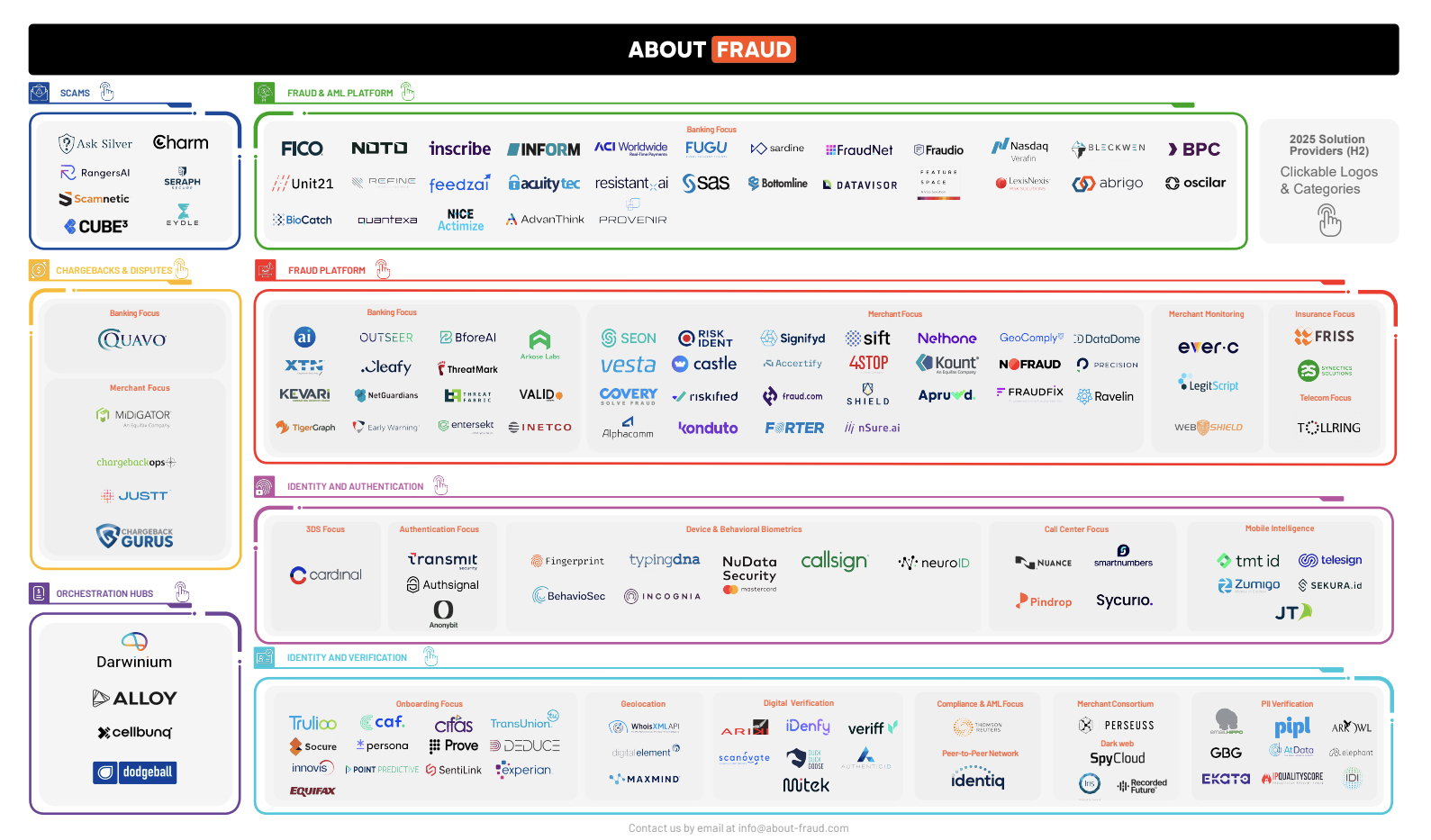

2025 Solution Providers Infographic.

We upped our game with our new Fraud and AML Solution Providers Infographic, breaking down all the solutions on our platform into categories that make sense. Download for free with newsletter signup.

Providers

A robust search tool for fraud solution providers. Customize to match your needs.

Resources

A curated list of resources for fraud education, content and associations.

Articles

The latest articles and content about fraud prevention from a global perspective.

Fraud Insight for a Global Community

About Fraud delivers unbiased, expert knowledge on technology and trends to a global community of fraud-fighting professionals.

A select list of global fraud solution providers. Customize your search.

A curated list of fraud consultants, training and certifications, and degrees.

Educate yourself with thought leadership and trending content.

Find fraud conferences with our events calendar and booklet.

Browse business opportunities for specific fraud professionals.

Stay ahead of best practices, the technology curve, and fraudsters.